I grew up learning to program in the late 1980s / early 1990s. Back then, I did not fully comprehend what I was doing and why the tools I used were impressive given the constraints of the hardware we had. Having gained more knowledge throughout the years, it is now really fun to pick up DOSBox to re-experience those programs and compare them with our current state of affairs.

This time around, I want to look at the pure text-based IDEs that we had in that era before Windows eclipsed the PC industry. I want to do this because those IDEs had little to envy from the IDEs of today—yet it feels as if we went through a dark era where we lost most of those features for years and they are only resurfacing now.

If anything, stay for a nostalgic ride back in time and a little rant on “bloat”. But, more importantly, read on to gain perspective on what existed before so that you can evaluate future feature launches more critically.

A blog on operating systems, programming languages, testing, build systems, my own software projects and even personal productivity. Specifics include FreeBSD, Linux, Rust, Bazel and EndBASIC.

First editors and TUIs

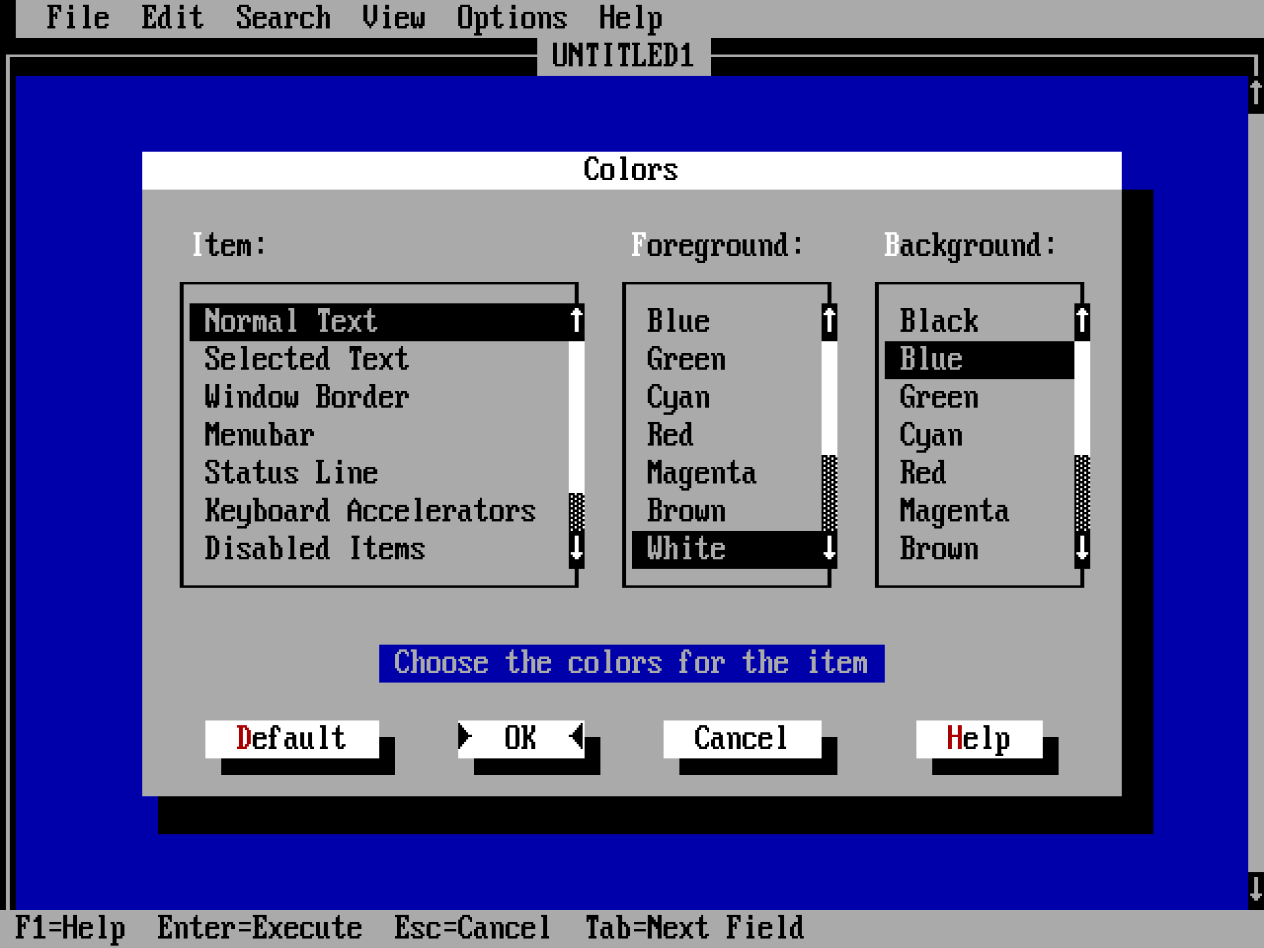

In the 1990s, almost every DOS program you ran had a full-screen Text User Interface (TUI) which sported text-based windows, drop shadows, colors, and mouse support. Here is just one example:

Each program was its own island because its interface was unique to the program. However, they were all so similar in how they looked like—80x25 characters didn’t leave much room for uniqueness—and how they worked that the differences didn’t really get in the way of usability and discoverability. Once you learned that the Alt key opened the menus and that Tab moved across input fields and buttons, you could navigate almost any program with ease.

But let’s talk about editors. MS-DOS shipped with a TUI text editor since version 5 (1991), which I previously covered in a recent article and is shown above. This editor “worked”, but it was really inconvenient for coding: you needed to exit the editor to compile and run your code, and when you re-ran the editor, you’d have to navigate back to where you were before.

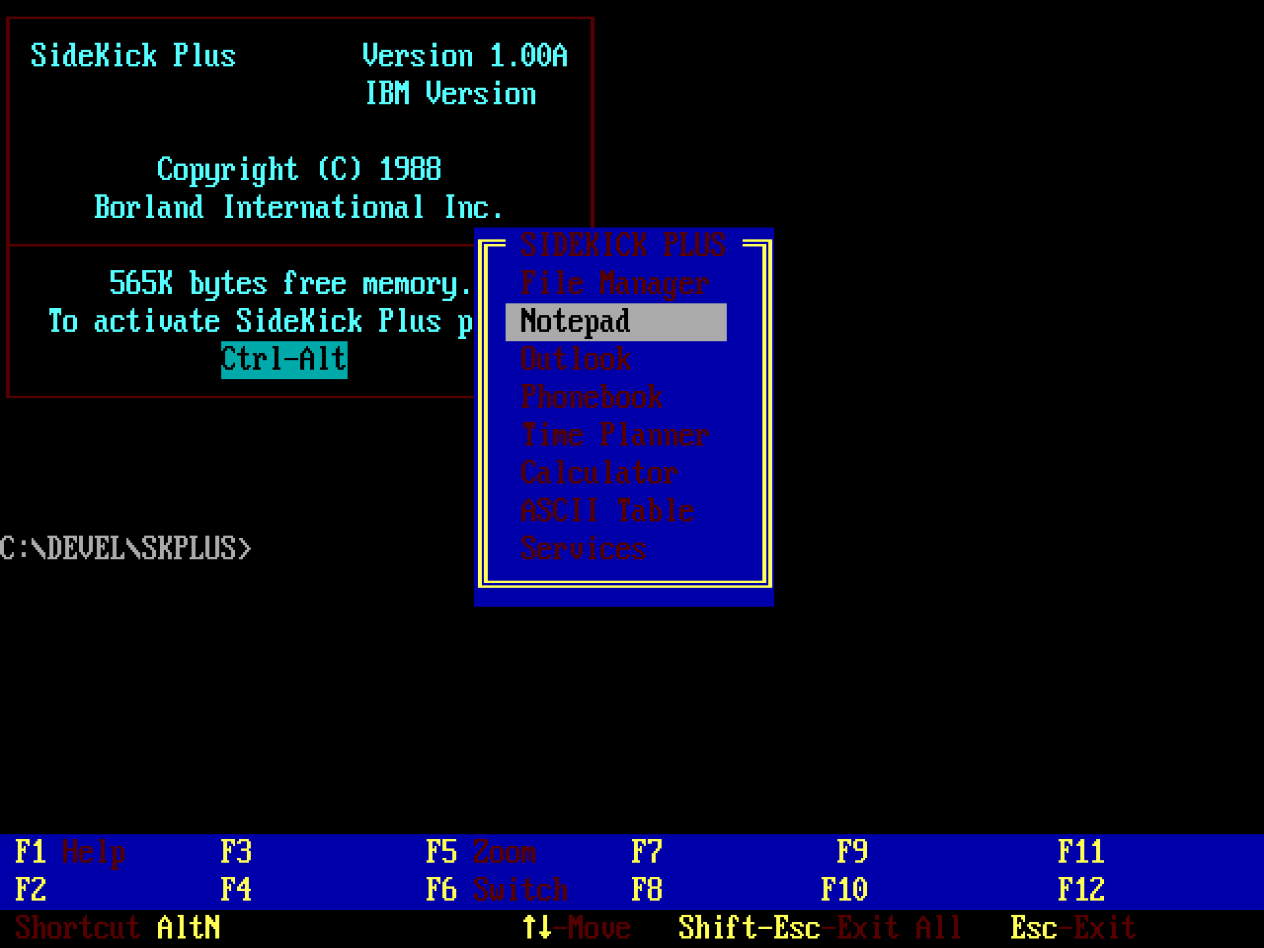

“In my house”, we used something called SideKick Plus (1984), which wasn’t really a code editor: it was more of a Personal Information Management (PIM) system with a built-in notepad. The cool thing about it, however, was that it was a Terminate and Stay Resident (TSR) program, which meant that it loaded in the background and you could bring it up at any time by pressing Ctrl+Alt.

Think of this TSR feature as rudimentary multitasking for an OS that did not have multitasking. This was really effective because quickly switching between code editing and building is critical for an efficient inner development loop. (And by the way, this past experience explains the design of the code editing flow in EndBASIC. I did not implement the equivalent of Ctrl+Alt, but I’ve considered it many times.)

By this point, however, real IDEs had already existed for a few years. Turbo Pascal 1.0 (1983) shows the beginning of an integrated experience, although it did not feature its iconic TUI yet. QuickBASIC 2.0 (1986) shows more of a “traditional” TUI (the same as EDIT.COM, because they are the same editor), and MS-DOS 5 came with QBasic, a reduced version of QuickBASIC that didn’t allow compiling to native code but that had the same look.

The Borland Turbo series

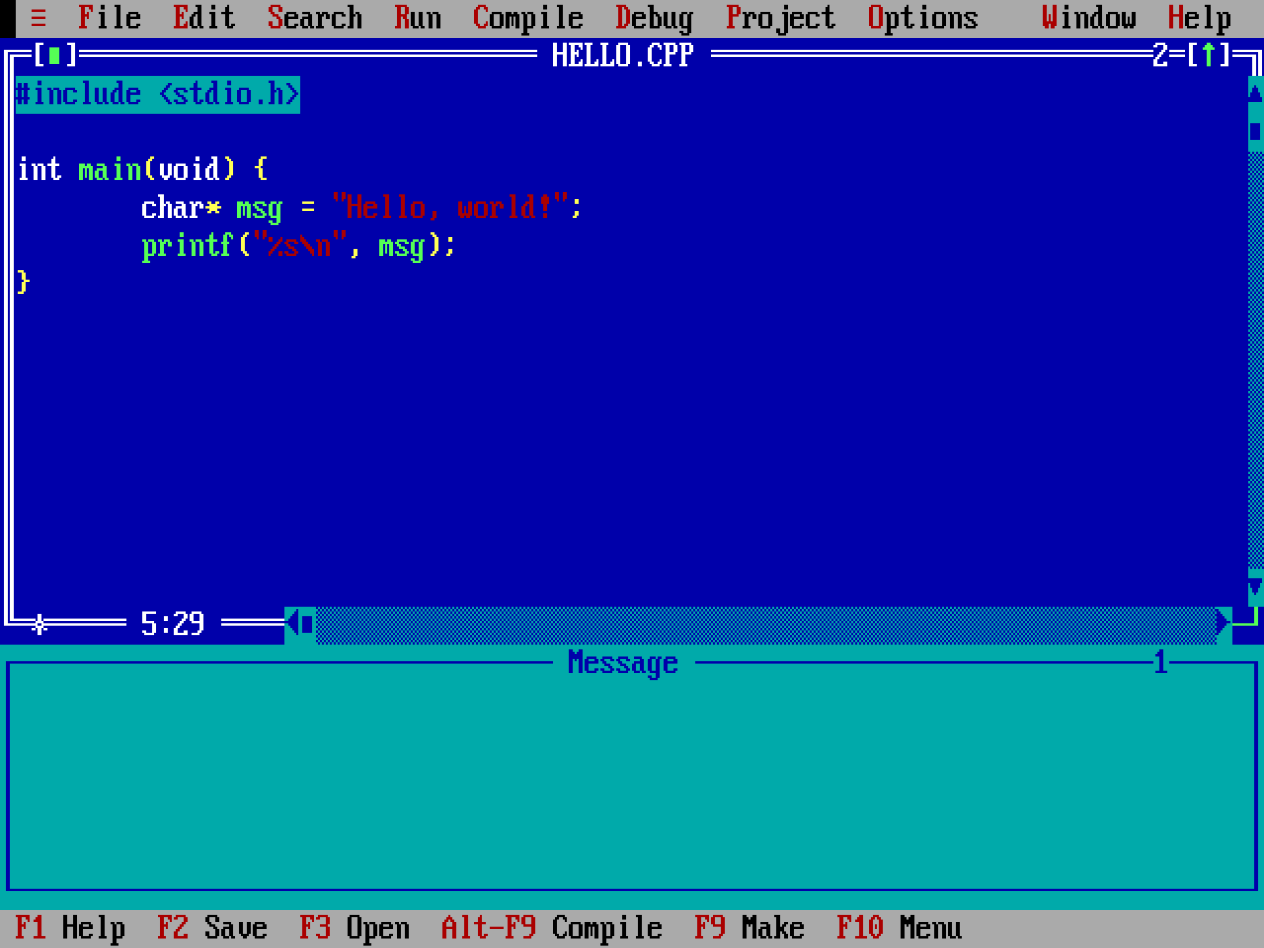

The crown jewel of IDEs, in my opinion, were the later Borland Turbo series, which included Turbo C++ (1990), Turbo Assembler and Turbo Pascal. These IDEs were language specific, but they had full-screen TUIs and were extremely powerful.

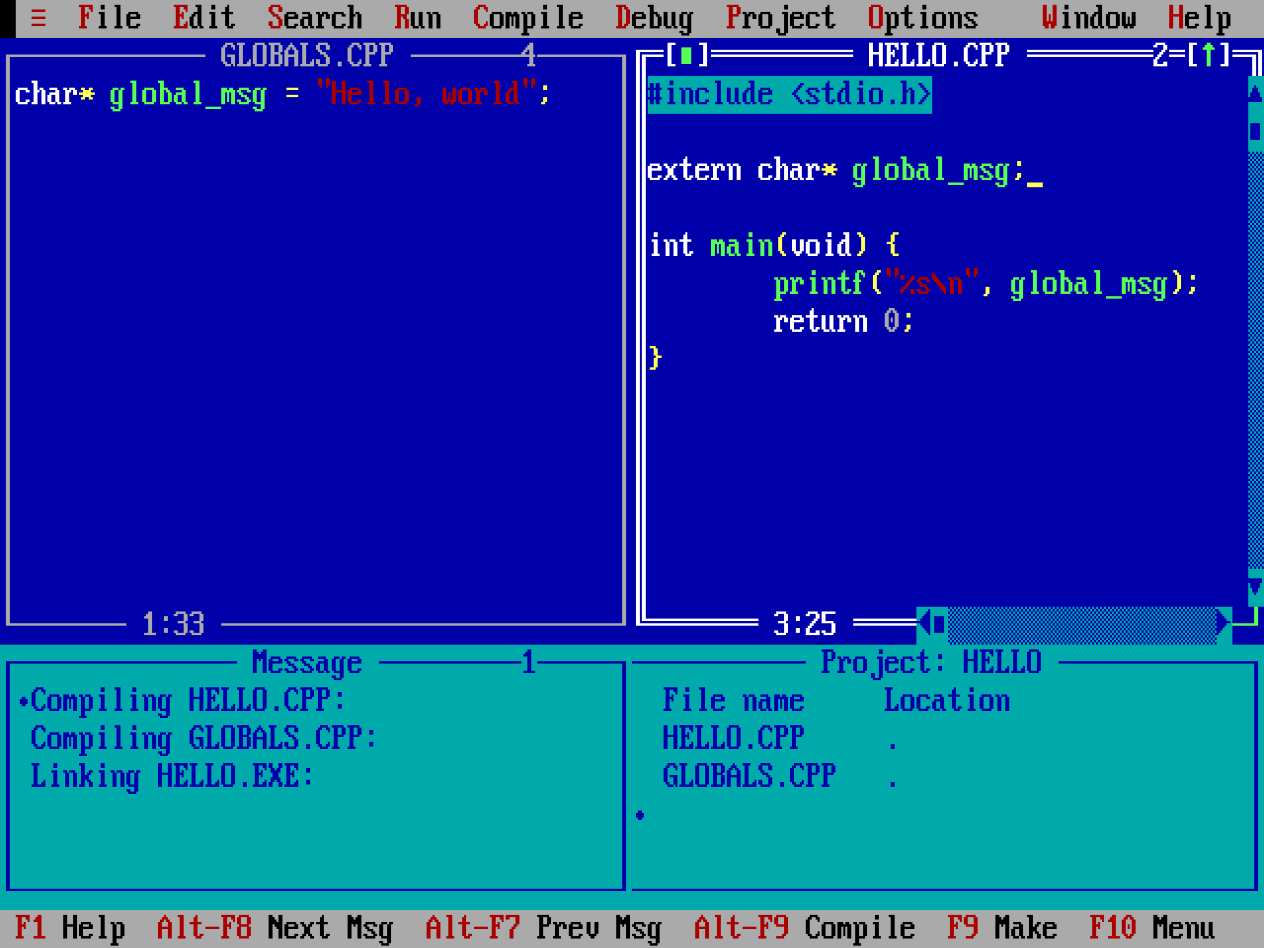

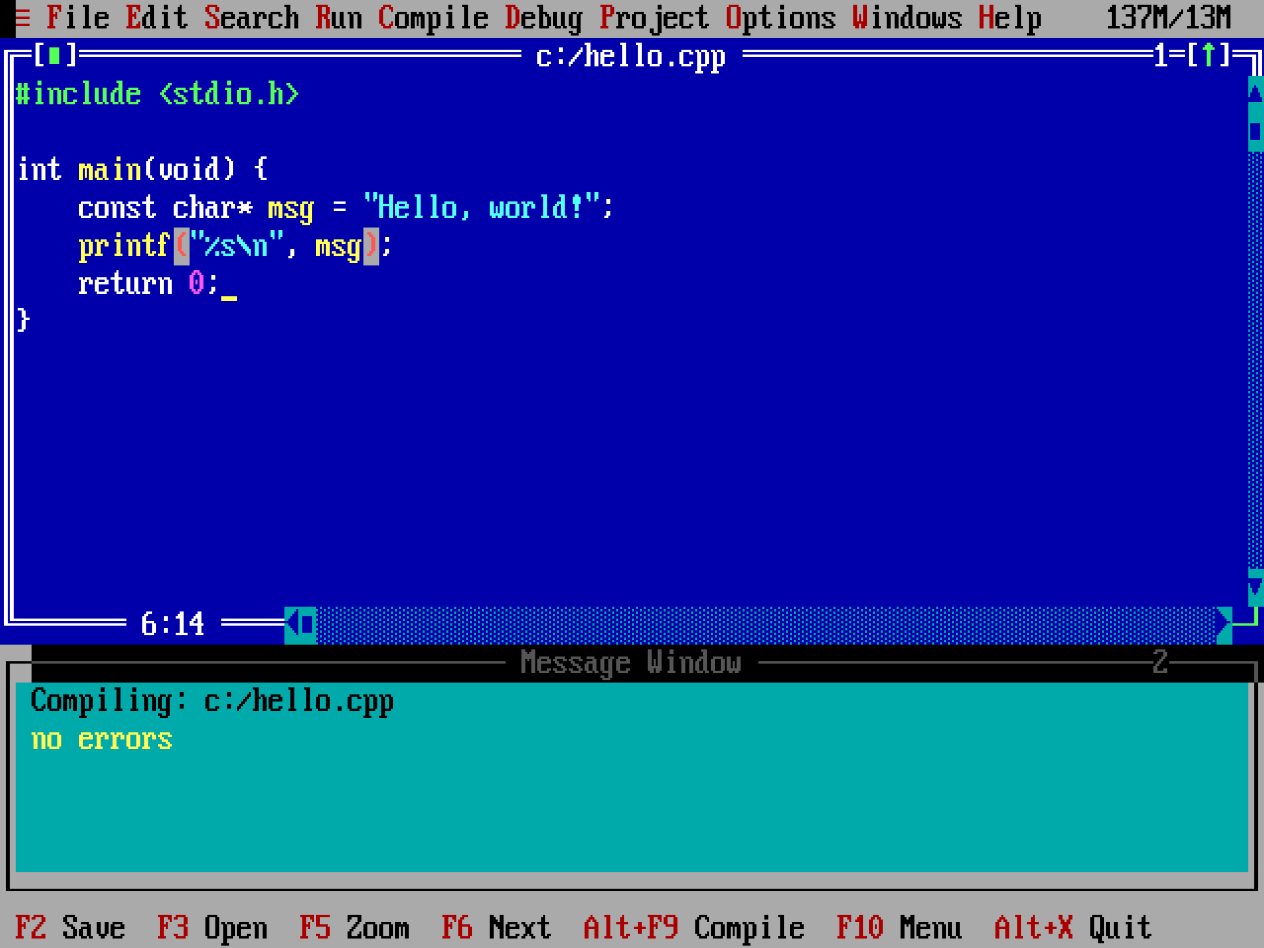

Here, take a look at what we had. Syntax highlighting:

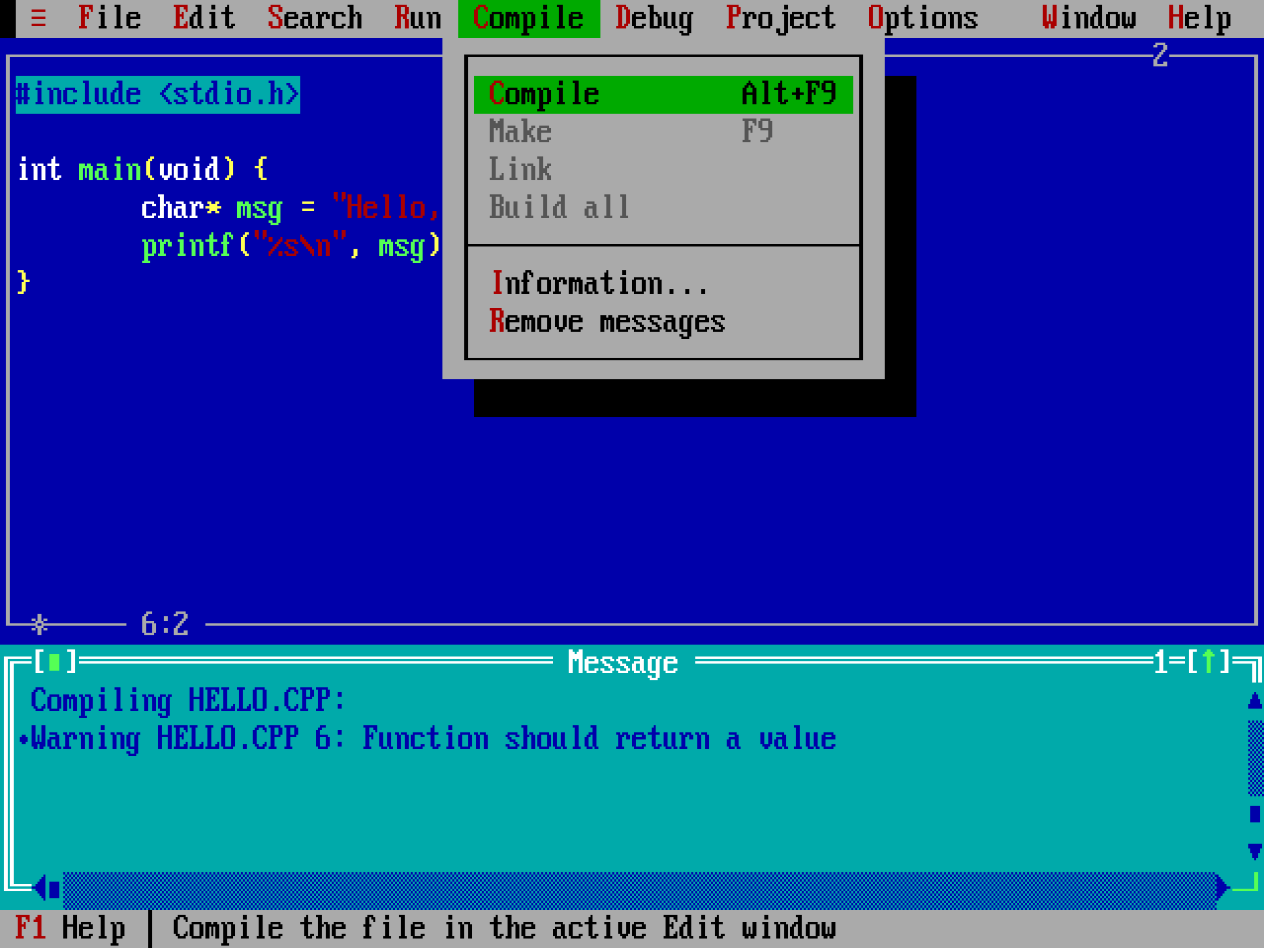

Compiler integration and diagnostics:

Integrated project and build system management:

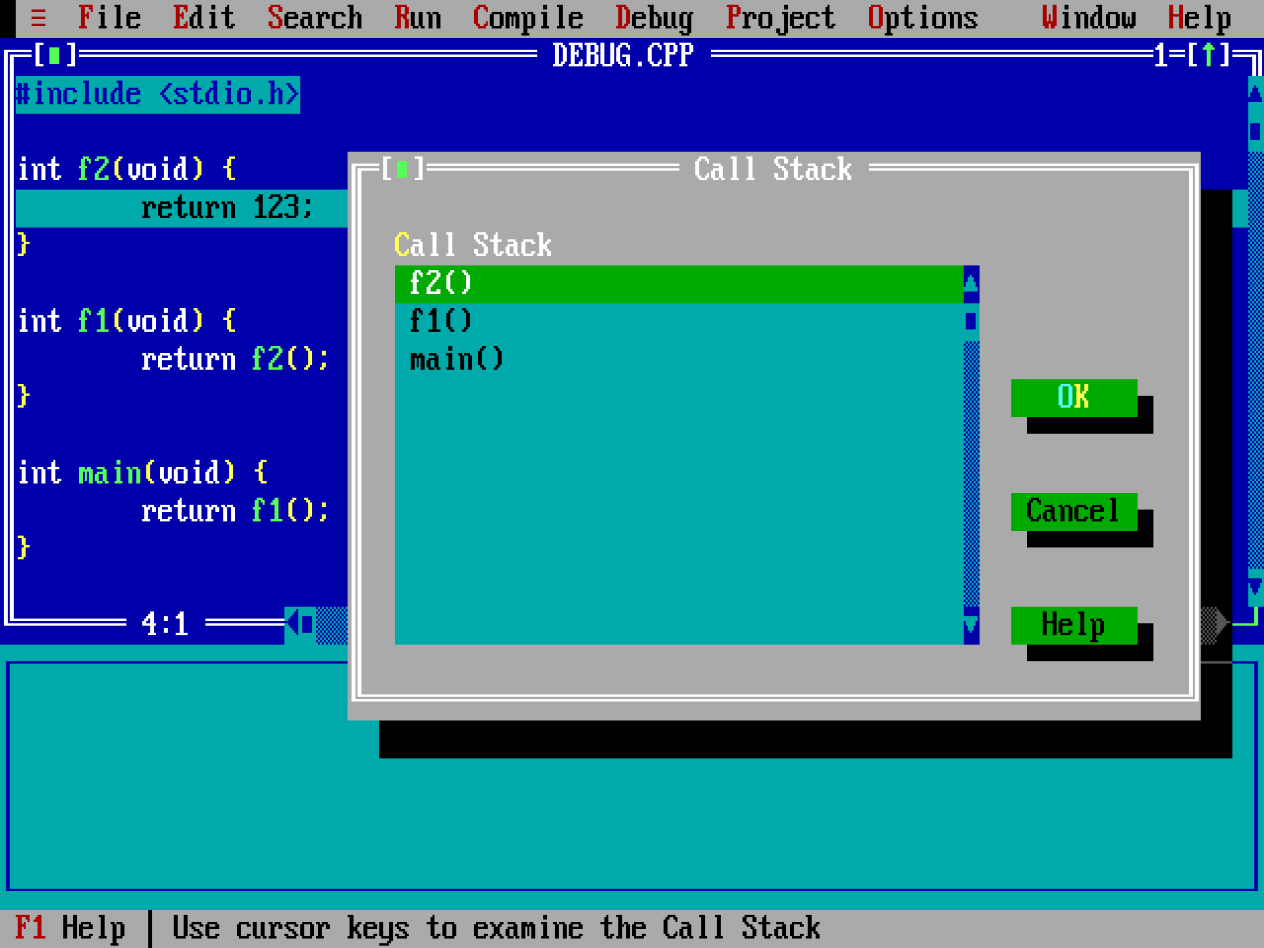

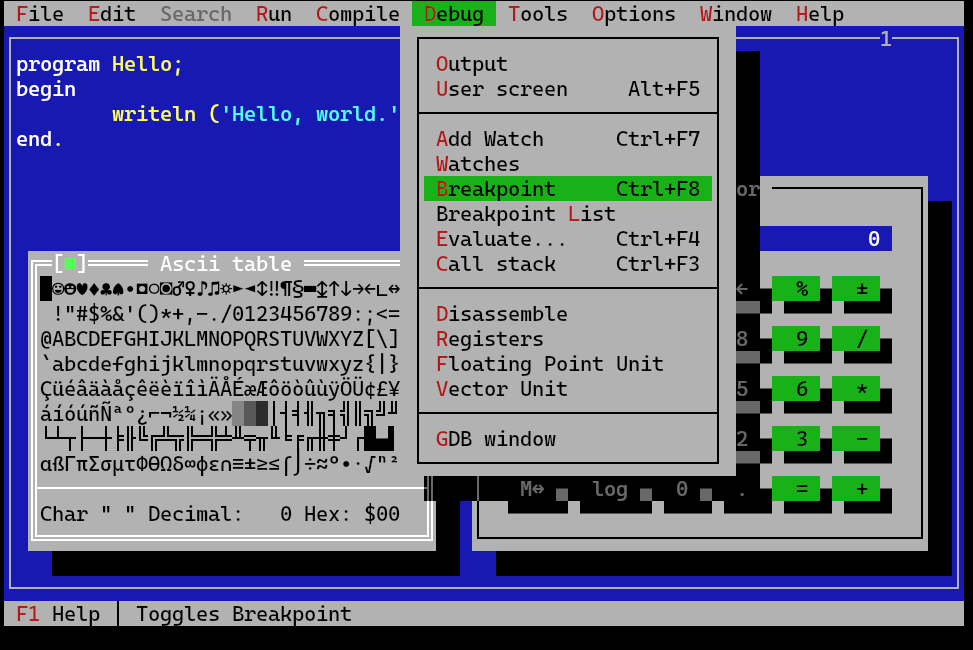

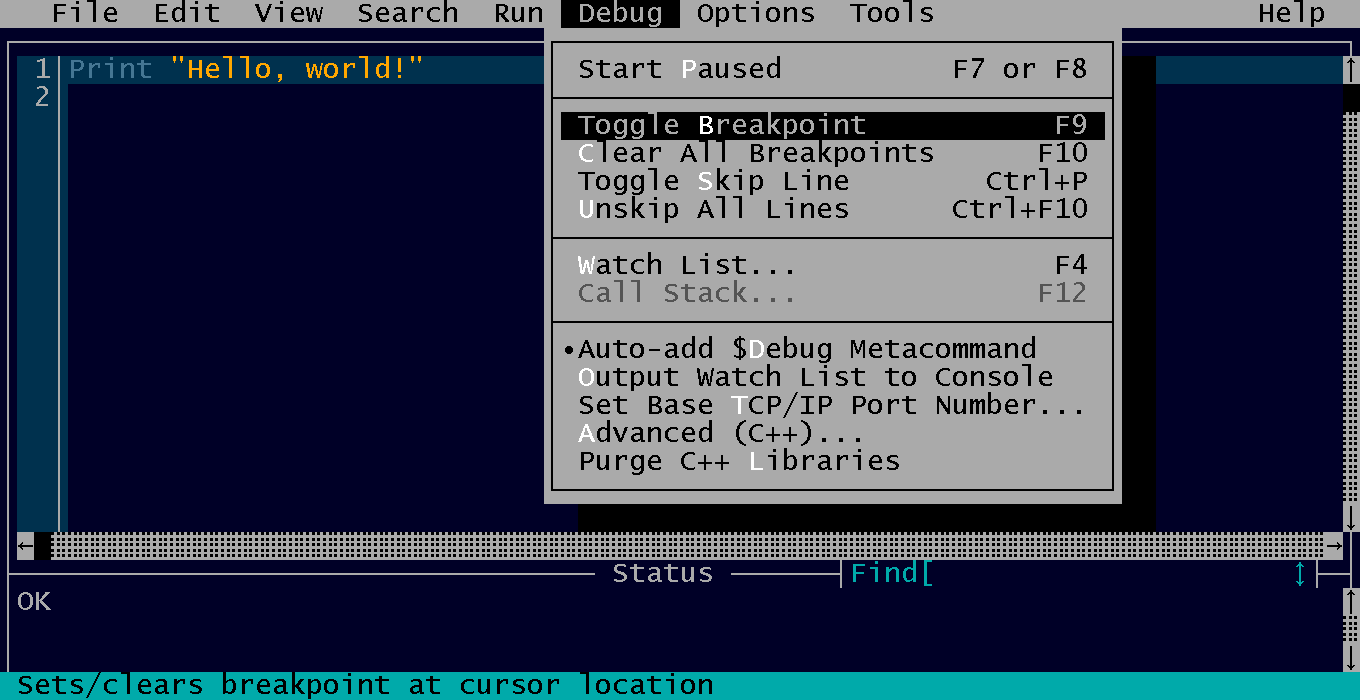

A debugger with breakpoints, stack traces, and the like:

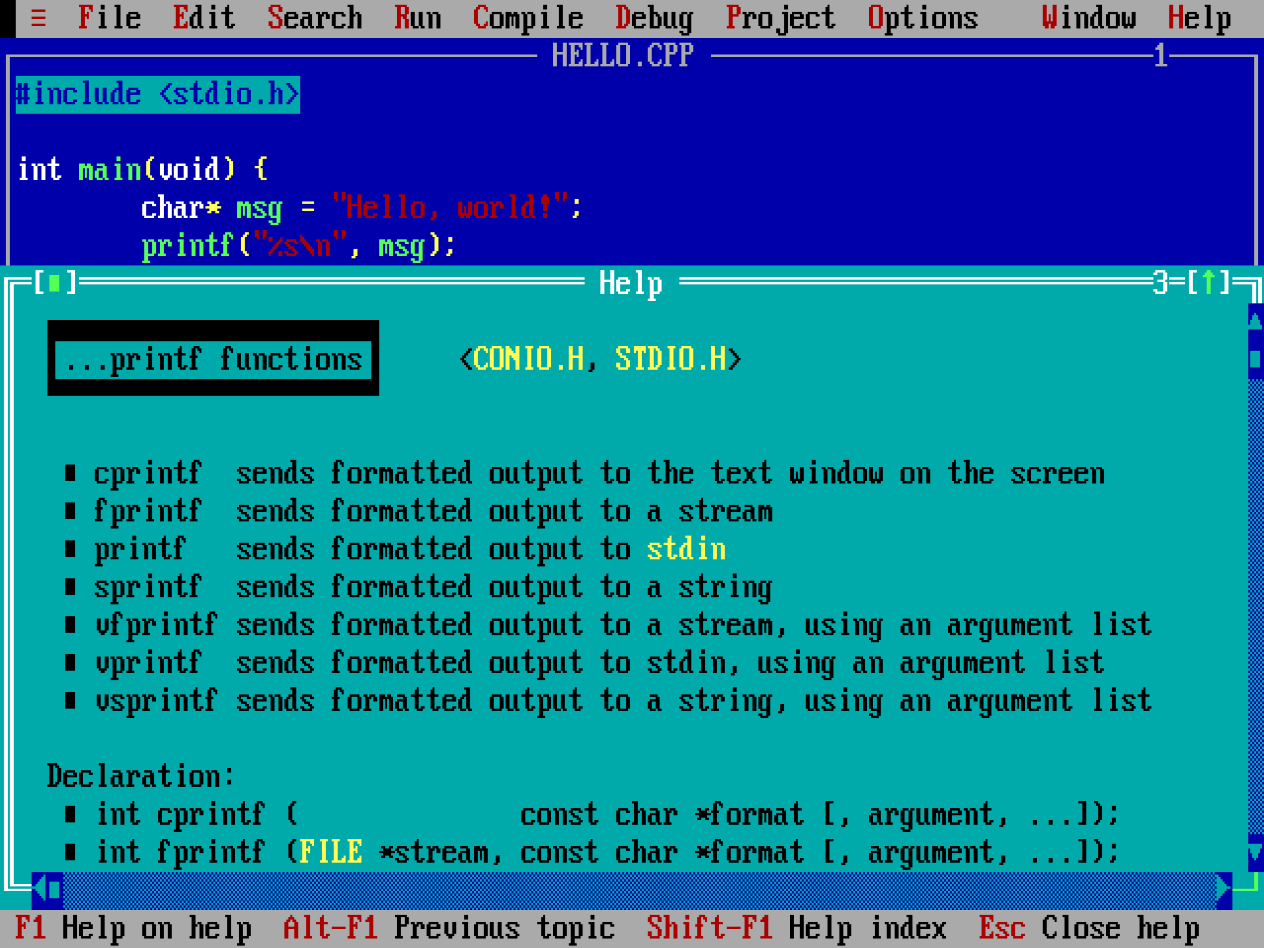

And even a full reference manual:

Remember: all of this in the early 1990s—a little over 30 years ago at the time of this writing.

I was an avid user of Turbo C++, with which I learned a lot. I remember using their conio.h libraries to implement TUIs of my own, and then their builtin graphics.h libraries to play with implementing GUIs. And note: this was without the Internet. There was no option for many to just “look up how things worked” in Stack Overflow: the IDE had to be discoverable right away (which it was) and self-contained to offer you a complete development experience.

What about Linux back then?

Now take a moment to compare this scene with Linux in the early 1990s.

In Linux, almost every program was also text based, but those programs did not come with a full-screen TUI. It just wasn’t “the Unix way”. I remember watching the X11 configuration tool (XF86Setup) or the OpenBSD installer and feeling shocked by how simplistic those were: me, a young teenager with barely any “real” coding experience, had written better-looking programs already.

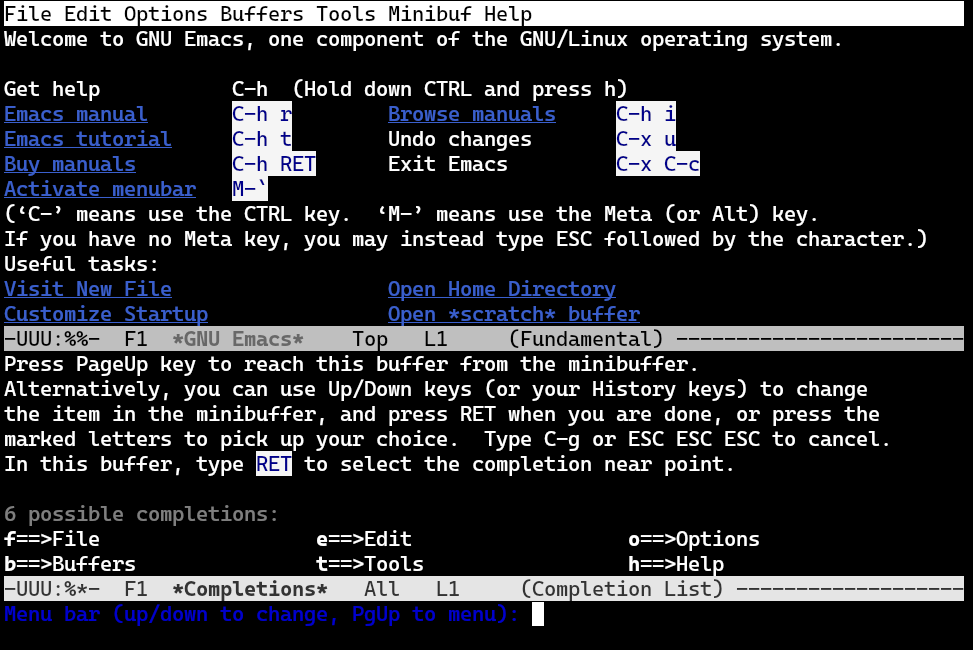

In any case, this didn’t stop me from my quest to not use Windows. I continued to learn the ways of Linux and soon faced the “best” editors recommended by every book and community online: Vim and Emacs. And I could not understand why they were praised. Using these was like stepping back into the past. They were full-screen programs indeed, but they seemed pretty arcane. Vim did have syntax highlighting but it was far from being an IDE. Emacs could be configured to integrate with some code assisting features and the like, but it was far from being “fire and forget” like the Turbo family of IDEs.

Just look at the default Emacs configuration today, which hasn’t changed much (if at all) since then. It does have windows, but they aren’t decorated. It didn’t have colors (and now barely has), because why? It didn’t use to have mouse support. It does have a menu bar though, but it is just a gimmick? If you press M-` as the instructions tell you, you face a truly strange interface to navigate the menu—which makes one wonder why they even bothered to waste a full line of screen real state to show a menu bar that does nothing.

Now try giving this to anyone with little coding experience and getting them to create, compile, and debug a program. They will have trouble just navigating the editor, and they won’t find any of the features that would allow for project management or compiler integration.

For comparison, in writing this post, I fired up Turbo C++ in DOSBox and I was able to create a “hello world” project and navigate the environment in minutes—all without prior knowledge (everything I had known has been forgotten by now). The environment is intuitive and, as an IDE, integrated all around.

Contemporary TUI IDEs

Anyhow. Let’s forget about the past and look at what we have today in TUI-land. I don’t want to look at GUIs because… well, Visual Basic was the pinnacle of graphics programming and we don’t have that either anymore—which is also a topic for another day. (Well, OK, you have Gambas… but who knows about it?)

The closest more-modern equivalent to the Borland Turbo C++ environment is RHIDE. As you can see in the picture below, it looks incredibly similar—and you’d be forgiven if you thought this is Turbo C++. Unfortunately, it is DOS-only and seems to be mostly abandoned by now with its latest release dated 7 years ago.

Then we have Free Pascal. This is the closest you’ll get to the old experience but with a modern codebase, running natively on Unix systems and leveraging terminals of any size.

And lastly we have QB64. This closely resembles Microsoft QuickBasic but… don’t let it trick you: even though it looks like a TUI, it is actually a GUI application that simulates a TUI. You cannot run QB64 in a terminal.

Both Free Pascal and QB64 are maintained and under relatively-active development, with their most recent releases in 2021… but they are mostly ignored because they expose arcane languages that most people have no interest in these days.

“Real” contemporary console IDEs

So what are we left with for modern languages today?

The state of the art seems to be Neovim, Doom Emacs, or even Helix. These editors are very powerful and, thanks to various plugins, offer reasonable IDE-like experiences. That said, if you ask me, none of these provide the same kind of experience that the previous Borland products offered: their interfaces are obscure and, due to their multi-language nature, they work OK for almost everything but they aren’t great for anything. “Jack of all trades, master of none” if you will.

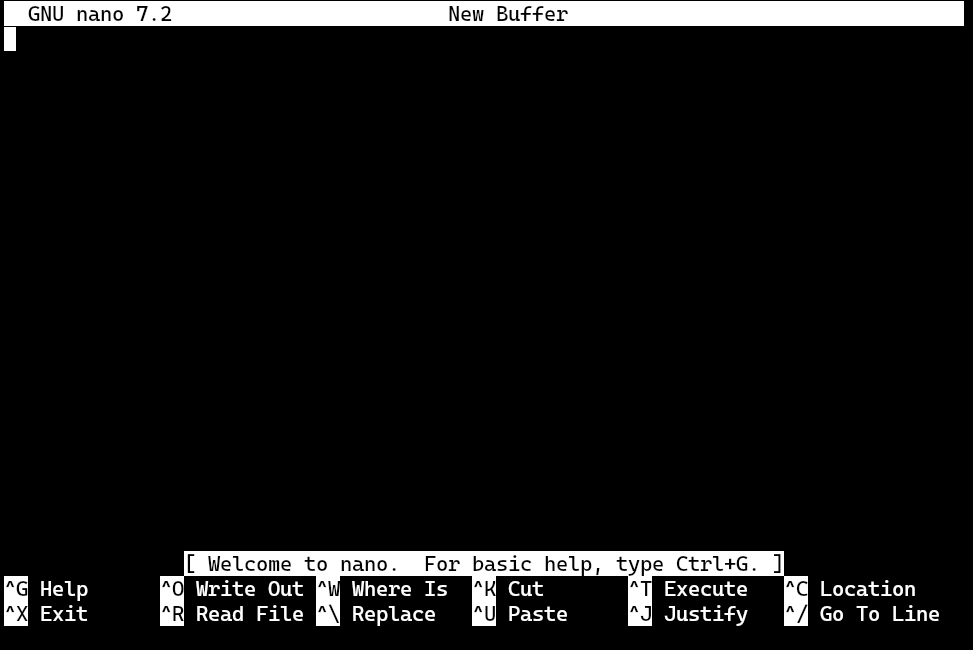

In any case, the preferred “simple” TUI editor, based on what I observed in the deranged microsoft/terminal#16440 discussion, seems to be… GNU Nano… which OK, it works, but first: it’s no IDE, and second, to me this looks like WordStar. Yeah, I know it isn’t WordStar: if you want WordStar, the closest you’ll find is Joe, but the looks of Nano remind me of my first experiences with a word processor back in the CP/M days. Here, look:

So even though we do have powerful console editors these days, they don’t quite offer the same usable experience we had 30 years ago. In fact, it feels like during these 30 years, we regressed in many ways, and only now are reaching feature parity with some of the features we used to have.

It is natural that TUIs diminished in popularity once graphical OSes gained traction, and it is somewhat interesting that they are making a comeback just now. As for why, I think we have to thank the invention of LSP for most of the recent progress in this area. TUI editors were “on hold” for many years because building IDE features for them was a lot of effort and their small maintainer base could not afford to implement them. LSP unlocked access to existing language-specific integrations and reinfused interest in the old-and-trusty Vim and Emacs. Hopefully, the upcoming BSP will do even more to make these TUIs more IDE-like.

Why TUI IDEs anyway?

It is fair to ask “Who cares? Every desktop and laptop runs a graphical OS now!”

And it’s a good question. In general, you probably don’t want a TUI IDE. If VSCode is your jam, its remoting abilities are superb and VSCode has a reasonably good graphical interface without being a full-blown IDE. But there are a few things that VSCode doesn’t give us.

The first is that a TUI IDE is excellent for work on remote machines—even better than VSCode. You can SSH into any machine with ease and launch the IDE. Combine it with tmux and you get “full” multitasking. Yes, you could instead use a remote desktop client instead of SSH, but I’ve always found them clunky due to lag and the improper integration with the local desktop shortcuts.

The second is that VSCode’s remote extensions are not open source, which isn’t a major problem… except for the fact that they don’t work on, say, FreeBSD and there is no way to fix them. So this makes it impossible for me to remote into my primary development server with VSCode.

And the third is… reduced resource consumption.

Bloat everywhere

I can’t leave without ranting about “bloat” for a little bit. Borland Turbo C++, with all its bells and whistles (the UI, the C++ toolchain, the integrated manuals…), is less than 9 MB after installation and ran within 640kb of RAM.

For comparison, Helix is 16 MB on disk, which is pretty impressive (and honestly unexpected), but Doom Emacs is about 500 MBs and consumes many MBs of RAM. Note, however, that none of these numbers account for the language toolchains or help systems, and toolchains nowadays rank in the GBs of disk space.

To get “real” IDEs, we have to jump to graphical programs like IntelliJ or VSCode. VSCode, for example, is about 350 MBs on disk (surprisingly less than Doom Emacs) but it will eat your computer for lunch: it’s Electron after all. I have noticed very significant savings in laptop battery life by dropping VSCode and moving to Doom Emacs.

So the question I want to part with is: have we advanced much in 30 years? Modern IDEs have some better refactoring tools, better features, and support more languages, but fundamentally… they haven’t changed much. The only major difference that we are starting to see might be AI-assisted coding, but this is a feature mostly provided by a remote service, not even by the installed code!

And that’s all for today. On my side, I’ll happily continue using all of Doom Emacs, Vim, VSCode, and IntelliJ depending on the situation. Merry Christmas if this is your thing!